Here we are at the end of a decade of low interest rates, in a much tougher fundraising environment than the heady highs of 2020-21, and a disjointed and uncertain economy. VC-backed CEOs like you are now coming to an inevitable realisation: if you don’t hit revenue growth targets, you’re unlikely to attract new investors. To make matters worse, existing investors may decide to allocate their finite capital to a different company.

While some of you will reach profitability and have plenty of options of where to go next, others will need to face reality as early as possible and consider selling the business.

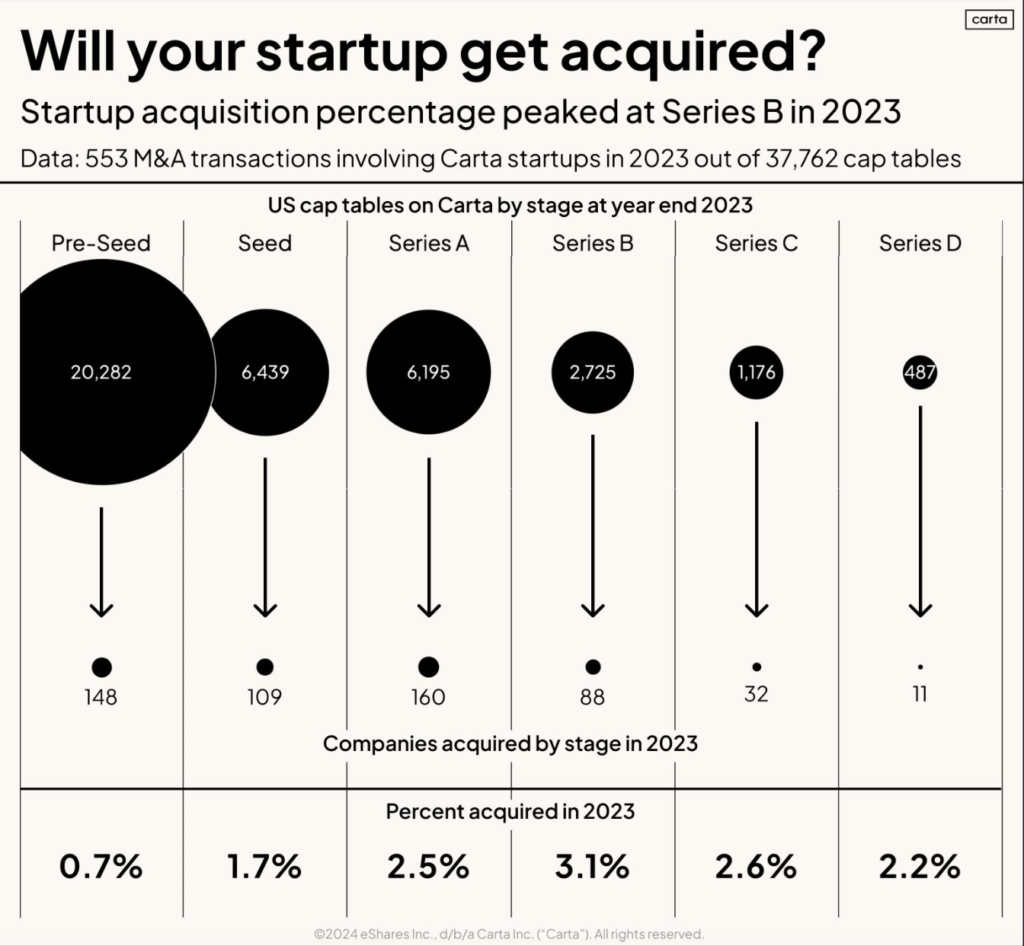

Much like the average bloke thinking they could land a plane in an emergency situation, many founders harbour the unrealistic expectation that they can ‘just sell’ their company if the original funding plan doesn’t work out. The reality is that getting acquired is really hard and really unlikely. The data tells us only a tiny fraction of companies actually get acquired.

And not to be completely doom and gloom, but even if you do get into a process with someone there is so much that can go wrong between signing the letter of intent (LOI) and closing the transaction.

Over the years, I’ve found myself acting as an independent counsellor to some incredible founders, and have now seen the M&A process play out a few times, noticing some common mistakes and frustrations at each stage of this process.

These mostly arise from a lack of communication between parties, and a failure to understand the different incentives at play. So I want to open source my learnings with the objective that more founders and senior leaders can be better prepared for this path, understand the behaviours of their stakeholders and hopefully maximise the outcome for everyone.

1) know which customers/partners are potential acquirers

No matter how well a business seems to be doing, it’s always best practice to know which of your customers or partners are potential acquirers. Then if the need arises, they are ‘warm leads’ and so much better than cold calling done by a corporate advisor.

For a customer, there are various qualifying criteria for when they might be an acquirer:

- Big spend and/or rapid growth indicating strategic importance

- Your product being something they have either tried and failed to build or talked about building

- You’ve already got relationships there with people who have revenue and growth responsibility etc.

There are corresponding ‘tells’ of partners to whom you may be strategically important e.g. you jointly win many/valuable deals together. If you never need to sell the business, then great, none of this ever arises—but it’s important to have in the back pocket. Another CEO may well end up saying to you ‘don’t sell this company without calling me first.’ Great result.

2) Find out early on if your investors are ‘buyers’ of your stock

It’s a very common tale; you’ve invested for growth—cash burn is high, runway is shrinking, and a few contracts are taking longer to close than you’d hoped. Do you know where you stand with your inside investors in a hypothetical future fundraise, or even in a bridge scenario? Have you openly talked about “what if all the great things we plan to happen, don’t”? If not, don’t assume you know the answer.

Once you’re operating at fewer than 18 months to cash out, you should address the following questions with your board/investor representatives. Realistically, at that point you are likely to get some vague responses but at 13 months runway, you really do have to seek out definitive answers:

- Do you think we can raise our next round as we stand today and on our current trajectory?

- Would you be supporting an additional investment into our business with your internal IC? (Are you a sell, buy or hold?) What are you ‘reporting back’ to the rest of your team when you talk about us?

- Do you have reserves set aside for us at this point?

- At what point would you expect us to be searching for an acquirer/engaging a banker?

The best outcome you can hope for in this scenario is alignment and clear communication (at a shareholder level) about the path forward for the company. So if the answers are fuzzy, push for clarity.

Being in limbo for any period of time is unpleasant, so even if the end result of this conversation is an agreement to try and sell the business, you can be comforted by having a singular goal to drive towards.

If investors are not planning to make funds available to you, you should understand that their incentive is to now facilitate a sale to — at the bare minimum — get back the money that they invested into your business.

3) You need a plan to get funded through the sales process itself

So, now you’re in sell mode. You must consider the question of whether you have enough cash to get to the end of a sales process.

Here are some things to bear in mind:

- 18 months runway is very useful, 12 months is doable—once you are inside 6 months, it’s almost impossible to get through a sales process. A potential acquirer who doesn’t put a lot of value on the team itself may smell blood and wait until you are really struggling to buy you out at a lower price. This all depends on what the acquirer values most about your business.

- Growth is likely to be knocked, given that certain key senior leaders will be concentrating on a M&A process (which can become all consuming). It’s one of the toughest dichotomies—you need the business to be growing in order to win over an acquirer (who won’t typically want to buy a flat-lining company) but revenue growth may suffer during this period, unless you run the M&A side of things extremely tightly. And, of course, if you do start growing like a rocketship again, your VCs (or other VCs) may once more be interested in funding the company. It’s a fine needle to thread.

- Often a company will want some more runway to get through a sales process.

Your existing investors: VCs won’t want to fund any further unless there is some kind of tentative offer or Letter of Intent (LOI) on the table. If your existing VC backers do decide to put forward funding, it is likely to come in the form of a convertible note. They do this instead of an equity deal because they don’t want to put a price on your business and set a new valuation anchor — the ideal outcome is that an acquirer decides your valuation in the coming months.

Similarly, VCs want to make an absolute minimum of a 3x return for every $ that goes out of their fund. They are unlikely to make that return by providing your company with funding at this stage, so instead they often attach a 2x redemption preference to the funding amount. This means that, if and when the business gets sold, this is the first money to be repaid and they will get 2x their money back (minimum).

Your existing debt providers: If you already have some venture debt in the business then it may make more sense to use this to fund the business through the sale process. Do the maths and never forget that, ultimately, most venture debt providers are like banks—they will do everything to be repaid.

The acquirer: Another option that is not uncommon but that may not be obvious is to have the potential acquirer bridge you to the final step of the process. Of course, this only becomes an option once you reach negotiation/LOI stage. It may feel like it weakens your position, but any potential acquirer will have seen your financials already as part of their due diligence, and it may be a simpler form of capital to raise than wrangling dollars from a fractious cap table via a punitive note. If the acquirer does lend capital, then it will wash out in the closing adjustments. Don’t forget, the acquirer of an early-stage startup is likely to be placing a lot of value on the team, so allowing payroll to be missed and key people to leave is a death spiral they don’t want to take place.

Again, you must have clarity here and alignment with your VCs on messaging to the market. Let’s say you have 8 months of runway and the prospective acquirer speaks to your lead VC. It’s the lead VCs job here to not say anything that would put off the acquirer. If the acquirer knows the business is running on fumes and that no one is interested in funding it, they may well just wait or pull out. I’m not encouraging any sort of misrepresentation here, but it’s this type of wrong move that can kill deals very quickly.

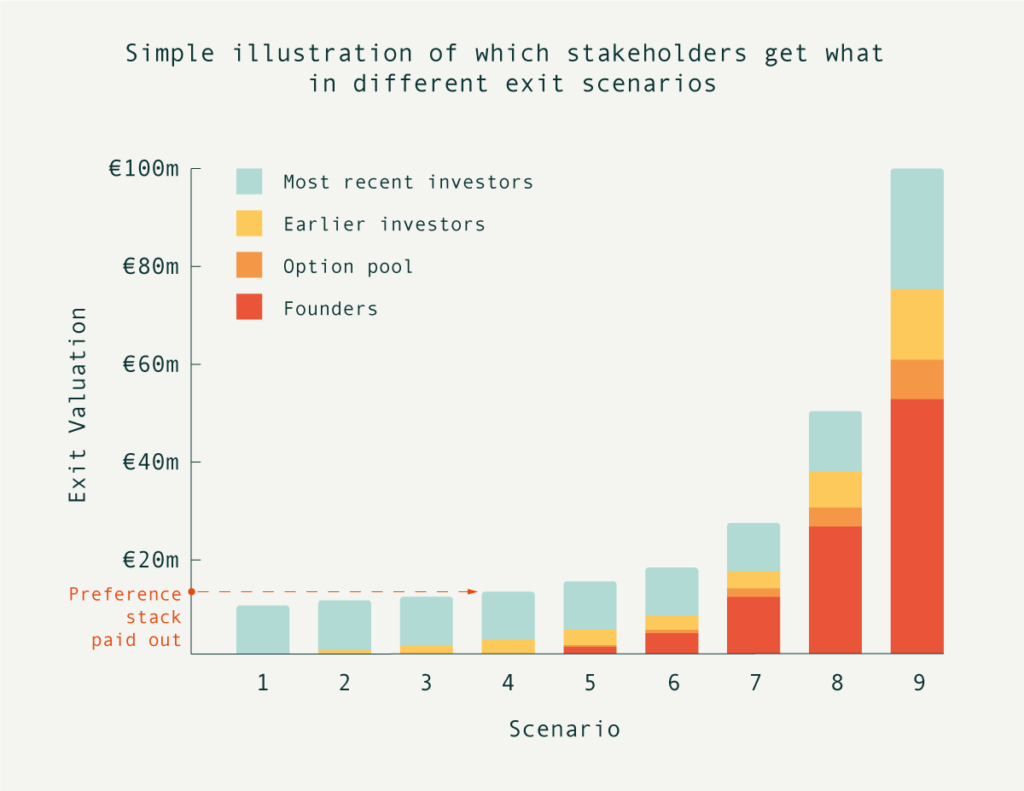

4) Figure out who gets what out of this sale

- Most recent investors: Big chunk of equity, top of waterfall, first equity holder to be repaid. Will want their capital back asap to deploy into other startups.

- Earliest investors: a good chunk of equity held, near to the bottom of the waterfall—either the same place or just ahead of the founders. Likely to have run out of funds to keep investing in the company and also most likely to end up ‘under water’ with nothing—the new owner doesn’t mind if early investors get zero, but they certainly don’t want the founders getting zero. Tough spot here—your earliest backers who took a chance on you can often get the most screwed. In scenarios 1-5 in the graph above, it would be likely that the acquirer would ‘re-cut’ the waterfall to ensure founders are receiving ‘meaningful’ proceeds (and not just the investors). So even though the legal documents may entitle the investors to get all of their money back, this may not end up happening and investors may agree to give up some of their proceeds to get the deal over the line.

- Employees: Smallest equity stake, bottom of the waterfall. Employees may lose their job (salary and benefits) and may or may not benefit from accelerated vesting of their options in a sale situation but, in all likelihood, they’ll transfer to the acquirer. The employees you need to be mindful of are those that are very valuable to the business—your CFO/COO/Chief of Staff is likely to become invaluable during a sales process and the acquirer will usually want the leadership team intact.

Founders: most equity at stake, bottom of the waterfall. Founders are typically vital to the success of the company and therefore the transaction itself. If there’s a buyer who likes what you’ve built, you are going to benefit. Most likely from the transaction proceeds and from growing the company in its new home. It makes no sense for founders to get zero/no incentivisation at all.

There’ll also be plenty of other claims being made on your “day one” distributable proceeds—corporate finance advisers, lawyers, accountants and then potential funds tied up in escrow for a certain period after the transaction has played out. Make sure you plug numbers into your waterfall early on to have an economic picture of where everyone stands — it will help give you a lens as to why you are getting the advice you are getting, or the questions being raised or why your pre-seed/seed stage investor feels a bit miffed.

If you’re using an equity management service like Carta then your waterfall should be readily available. If you’ve built your own model then have it double and triple checked—both by a lawyer and a VC (typically a legendary associate can help do this), independently. Home-grown models are usually wrong (sometimes very wrong) in their first version.

5) Put yourself in an acquirer’s shoes and listen to valuation advice

When it comes to valuing your company, know that your acquirer is not looking at your business through the same lens that you do.

There are basically three buckets for acquisition prices:

- Invested capital plus a bit (for an acquihire, distressed sale). The team’s outcome then is mostly on the back end through earn-outs and time at the acquirer.

- Multiple of this or next year’s revenue (for a company which isn’t a forced seller, has a good team/IP and/or where the situation is competitive)

- crazy AI prices (self explanatory!)

Going into a sale process with a lofty opinion of how your company should be valued may backfire—rejecting an early offer that feels too low may prolong the process to the point that you’re out of cash and the original offer is off the table. Get each of your large shareholders (founders, VCs) to tell you what they consider a ‘fair’ valuation of your business to be. They’ve been valuing the business for internal purposes once a quarter so they should have this information readily available.

Think critically about why a buyer/key sponsor within the buyer would put their neck on the line to buy this company. How does it make sense as a business case for what she (and her company) are trying to achieve?

Taking a punt on a seed-stage company is rarely the answer, and most companies can’t sensibly buy pre-series A startups (unless they are simply buying the team or IP). They want revenues, a customer base, brand and product already built out so they can bring their own sales and marketing to bear.

Don’t forget, the buying company will be taking on a big working capital burden to get a newly acquired business to wash its own face (and not be a drag on their balance sheet)—No buyer finds a high-burn, high head-count company an attractive proposition, even with the best technology/product in the world.

And one last point I’d make is that the reality is that most big companies screw up M&A integrations. It’s likely that in a year the acquired team will mostly leave, that ambitious revenue goals won’t have been hit (and you will feel it’s because you didn’t get the attention/resources/sales bandwidth etc you were expecting), and the product plan and product integration milestones will be missed. So, where you have discretion, don’t tie too much of your transaction to earn-outs based on ambitious and optimistic goals.

Happy to write more/chat more on this topic – let me know what interests you. There’s tons of rabbit holes I could go down!